Introduction

Before diving into this post, I’d like to preface it with a disclaimer. I’m not a historian, nor would I call myself an accomplished writer. What I share here isn’t intended to provide definitive answers or settle any debates about these ancient stories. Instead, my hope is to open up the conversation, spark curiosity, and perhaps reignite a sense of wonder for those who choose to revisit these timeless myths.

I’ve been fascinated by history and myths for as long as I can remember—a passion that began in childhood and has only deepened over the years. It all started with the legend of King Arthur and gradually expanded to include epics like Beowulf, The Iliad, The Odyssey, as well as many others.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve often felt that the world has lost much of its wonder. The maps have been drawn, the lands explored, and the mysteries conquered. In childhood, imagination knows no bounds and anything seems possible, from magical realms to heroic quests. But with age comes a quiet disenchantment. You begin to realize that there is no magic, no daring adventures into the unknown, and no divine mysteries waiting to be uncovered. The stories of epic heroes, fearsome monsters, and vengeful gods reveal themselves as just that—stories, woven from the fabric of human imagination.

But what if some of these stories aren’t just stories? What if there’s some semblance of truth in them, no matter how small? While I won’t claim that Beowulf truly slew a fire-breathing dragon or that Sir Palamedes hunted the elusive Questing Beast, I’d like to take the time to explore each tale and investigate the realities behind them, however faint.

Through this journey, I hope to rekindle a sense of wonder for those who read these stories—knowing that there may be a sliver of truth within them. Whether they’re inspired by real people, rooted in historical events, or simply reflections of the lives, beliefs, and cultures of their time, these tales still have something profound to teach us.

The Story of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh follows Gilgamesh, the King of Uruk, described as two-thirds divine and one-third mortal. He is the son of the goddess Ninsun and the legendary king Lugalbanda. At the outset, Gilgamesh is a proud and oppressive ruler who abuses his power, forcing his people to endure his tyranny. Desperate for relief, the citizens of Uruk cry out to the god Anu, who commands the creation of Enkidu, a wild man fashioned by the goddess Aruru to serve as Gilgamesh’s equal and counterbalance.

Enkidu lives among the animals in the wilderness, disrupting hunters and protecting wildlife. A trapper, frustrated by Enkidu's interference, seeks help from Gilgamesh, who sends a temple prostitute named Shamhat to tame him. Through her, Enkidu gains knowledge of human ways, losing his connection to the wild but gaining self-awareness. After hearing of Gilgamesh’s oppressive rule, Enkidu travels to Uruk to confront him. The two engage in a fierce, violent battle that spans the streets of the city. Neither emerges victorious, but they come to respect each other’s strength and form a deep bond of friendship.

Together, Gilgamesh and Enkidu embark on heroic adventures. Their first great quest takes them to the Cedar Forest, where they face Humbaba, the monstrous guardian of the forest. Though Humbaba pleads for mercy, the two heroes slay him, defying the gods who appointed him as protector. They cut down the sacred cedars and return to Uruk with the spoils of their conquest.

Their next trial arises when the goddess Ishtar, impressed by Gilgamesh’s bravery, proposes marriage. Gilgamesh rejects her, listing the fates of her previous lovers and mocking her cruelty. Furious, Ishtar convinces her father, Anu, to send the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh. The Bull wreaks havoc on Uruk, but Gilgamesh and Enkidu join forces to slay it. In an act of defiance, they hurl the Bull’s severed haunch at Ishtar, further enraging the gods.

The gods decree that one of the heroes must pay for these transgressions. Enkidu falls gravely ill, tormented by dreams of the underworld and the gods’ judgment. After days of suffering, he dies, leaving Gilgamesh stricken with grief. Enkidu’s death marks a turning point for Gilgamesh, who becomes consumed by fear of his own mortality. Unable to accept the inevitability of death, he sets out on a quest to discover the secret of eternal life.

Gilgamesh’s journey takes him to the ends of the earth. He ventures through treacherous landscapes, including the twin mountains Mashu, whose gates are guarded by scorpion-men. Beyond the mountains lies the Garden of the Gods, where Gilgamesh meets Siduri, a divine tavern-keeper. She advises him to abandon his quest and embrace the joys of mortal life, but Gilgamesh refuses to relent.

Siduri directs him to Urshanabi, the ferryman of Utnapishtim, a man who was granted immortality by the gods after surviving a great flood. Gilgamesh convinces Urshanabi to guide him across the Waters of Death to meet Utnapishtim. When they meet, Utnapishtim recounts the story of the flood, a tale strikingly similar to the biblical account of Noah. He explains that immortality is a gift reserved for the gods and that humans must accept their finite existence.

Despite this, Utnapishtim offers Gilgamesh a chance to prove himself worthy of eternal life by staying awake for six days and seven nights. Gilgamesh fails the test, succumbing to sleep almost immediately. As a consolation, Utnapishtim tells him of a plant at the bottom of the sea that can restore youth. Gilgamesh retrieves the plant but loses it to a serpent on his journey home, symbolizing the fleeting nature of life and the inevitability of death.

Humbled and transformed by his journey, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk. Standing atop its great walls, which he once built, he finds solace in the enduring legacy of his city and his deeds. He accepts his mortality, recognizing that his contributions to civilization will outlive him.

Myth Meets Reality

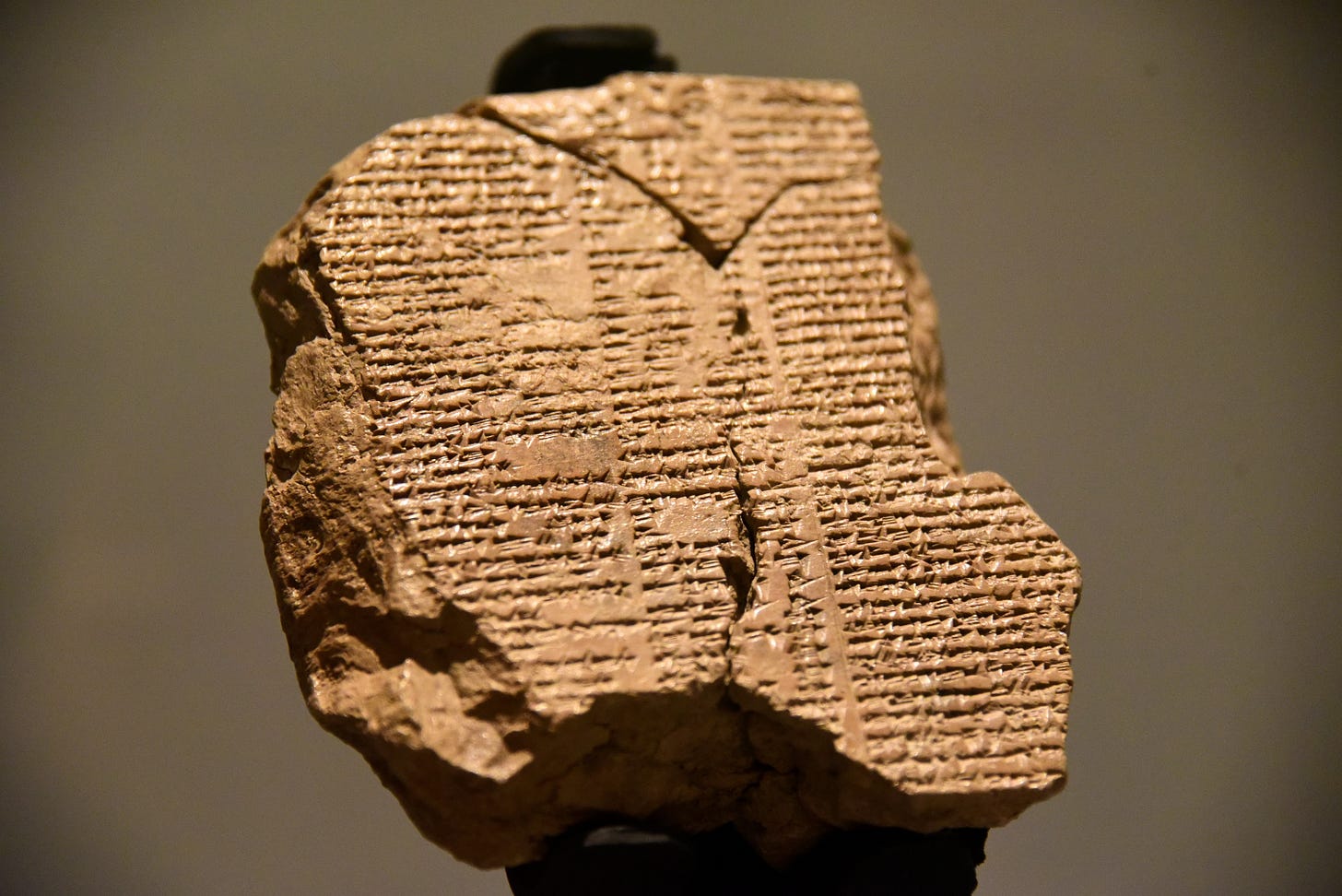

The Epic of Gilgamesh is widely regarded as one of the oldest surviving works of literature, dating back to the Bronze Age—a pivotal era in human history that saw the advent of the earliest known writing systems. Inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform script, it was rediscovered in the 19th century during excavations of the Library of Ashurbanipal in modern-day northern Iraq.

While the Epic of Gilgamesh straddles the line between myth and history, many scholars believe he may have at least been inspired by a real King of Uruk who ruled around 2700 BCE. The city of Uruk, located east of the Euphrates River in southern Iraq, was identified in 1912 and is often regarded as one of the world’s first major cities. According to the Sumerian King List, an ancient document recording the reigns of Sumerian rulers, Gilgamesh is listed as one of Uruk’s early kings, ruling sometime between 2900 and 2350 BCE.

Further evidence comes from the Tummal Inscription, an old Babylonian tablet from around 1900 BCE, which credits Gilgamesh with constructing the walls of Uruk and rebuilding the sanctuary of the goddess Ninlil in Tummal. Additionally there is the poem of Gilgamesh and Aga, that contains no mythological elements, describes a conflict and subsequent siege of Uruk by Aga of Kish. While it's unclear if this ever truly occurred, its focus on a historical setting strengthens the case for Gilgamesh.

Though the portrayal of Gilgamesh as a superhuman hero communing with gods is undoubtedly mythical, there is some compelling evidence to suggest he was a historical ruler of Uruk. The Epic of Gilgamesh itself may have been crafted to legitimize his rule by attributing divine ancestry, a common practice in ancient Mesopotamia. This blending of fact and myth allowed Gilgamesh’s legacy to endure as both a historical king and a timeless epic hero.

Why It Still Matters

The Epic of Gilgamesh isn't just a historical artifact, it's a story that has shaped literature for millennia. Its exploration of mortality, legacy and the meaning of life feels as relevant now as it did thousands of years ago.

Gilgamesh's journey is an early example of the hero's journey, a narrative structure that continues to influence storytelling. His struggles with grief and search of purpose echo in works ranging from Homer's Iliad and Odyssey to more modern fantasy like J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. While claims of direct influence on these writers may be overstated, the epic’s exploration of heroism, friendship, and mortality aligns with themes that recur across cultures and eras. It serves as a reminder that the questions and struggles of ancient peoples are not so different from our own.

What makes the Epic of Gilgamesh endure is its ability to connect with universal human experiences. It asks questions that still resonate. What does it mean to live a meaningful life? How do we cope with loss? What kind of legacy do we leave behind?

Revisiting this ancient tale isn’t just about understanding the roots of storytelling, it’s about recognizing that, despite the passage of millennia, our hopes, fears, and desires remain remarkably similar. The Epic of Gilgamesh is more than a tale of gods and kings, it’s a celebration of the human spirit and its capacity to endure.

Ramblings

Thank you for taking the time to read my first blog post. I’d love for you to join in on the conversation, so feel free to share your favorite myths, suggest a book for me to read and review—particularly one that you believe is overlooked or underappreciated. And with that, I hope you all have a wonderful week and I hope to hear from you all soon.

Read More!

Check out my next article on Beowulf!